A Venice For The Next Century: NYC And Climate Change

By Lily Rothman and Kara Bloomgarden-Smoke

Rising water levels will be one of the most noticeable components of climate change, particularly in a city like ours with more than 500 miles of shoreline in the five boroughs.

In fact, it already is: the water that surrounds Lower Manhattan, according to the city’s panel on climate change, has gone up by more than a foot since the beginning of the twentieth century.

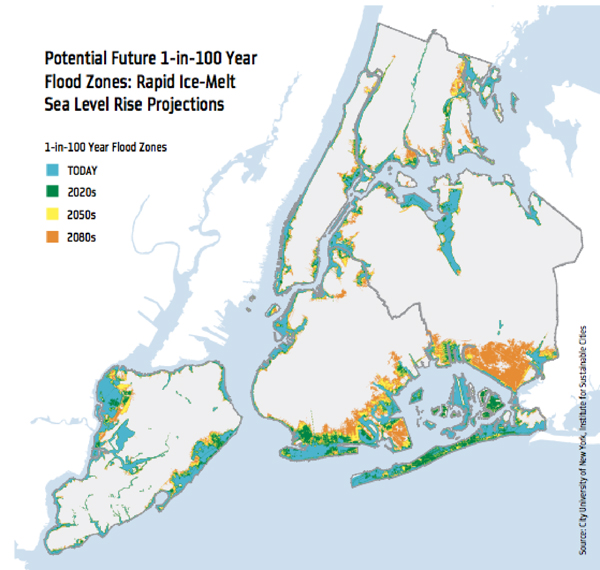

Flooding is already more frequent. So-called 100-year floods are now predicted to occur every 80 years.

There’s a lot of science behind why the water is rising, but basically hotter temperatures mean melting ice, which means higher sea levels. As the water rises, coasts that were previously at sea-level elevations will be submerged.

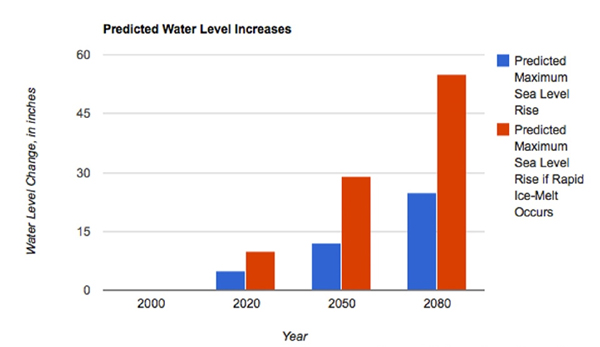

Scientists predict that water levels could rise by up to 23 inches in the next 75 years—and that’s if there is no rapid glacial ice-melt in the arctic. If that melt continues at the rate of acceleration it has attained today, that figure could go up to 55 inches.

In response, Mayor Bloomberg convened the New York City Panel on Climate Change, as part of the larger PlaNYC initiative in 2008. The panel released a report two years later.

In addition to making those dire predictions about rising sea levels, the panel found that the existing FEMA flood-plain maps for New York City are outdated.

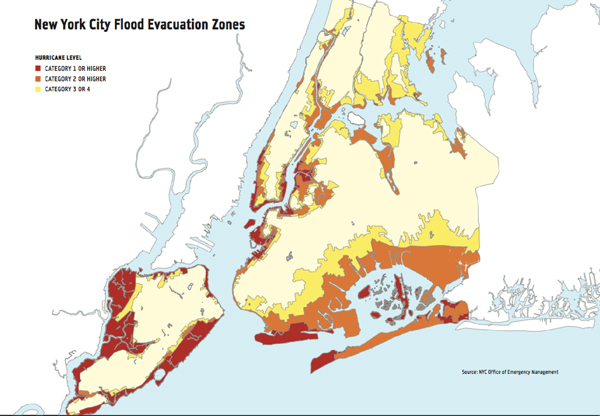

Those FEMA maps show which areas are subject to 100-Year Floods, a measure of the frequency of major flooding, which is used to determine everything from insurance premiums to city-planning regulations. The coast of Lower Manhattan is already in the flood zone. Within fifty year, the Panel predicts, that zone will move toward Broadway, especially in low-lying areas like Canal Street.

Floods will interfere with subways and sewers, but if the water rises by the amount that is predicted, the city will be dealing with that water all the time.

But what does 23 inches of water look like? Click on the place marks in this map to see what 23 inches of water would mean at various places in Lower Manhattan:

View Climate Change in NYC in a larger map

What about a wall to keep the water out?

Although this seems like an intuitive solution, it isn’t a good enough plan.

At most, say scientists, it would provide a temporary solution to a permanent problem.

According to VISION 2020: NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN, Dikes and levees, “can provide substantial protection from flood waters for a larger area but also bear a range of costs, can alter ecological functions, and still may be over topped by a flood or storm surge exceeding their designed capacity.”

“The estimate is only accurate to a certain extent, and the problem with a wall is that it could go over the wall and get trapped behind,” said climate scientist Rae Zimmerman, who served on the city’s panel. “That’s what happened in Japan with the tsunami. They had a new sea wall, but the water went over it and got trapped and couldn’t drain.”

If water gets higher than the structures, the results can be disastrous – as seen in New Orleans or Japan.

Can flooding be prevented?

One idea: Re-vegetate the wetlands.

Many scientists point to the creation of wetlands as a possible solution to help soak up the extra water that will be caused by rising tides.

“They’re also thinking about re-vegetating wetlands so it retards the flooding,” said Zimmerman. “Wetlands are wonderful.”

According to Climate Change Information Resources, “The Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) carries out numerous projects around the New York metropolitan region that aim to counteract beach erosion, reduce flood damage, and restore natural wetlands and estuaries, some of which explicitly include climate change.”

However, it is impossible to re-vegetate enough wetlands in an urban area and the projected levels of water may be too high to be absorbed.

And while these consequences of climate change may seem far off, unless steps are taken soon – it will be too late.

In short: No, rising water levels can’t be prevented, at least not by the city.

May 4, 2011

May 4, 2011